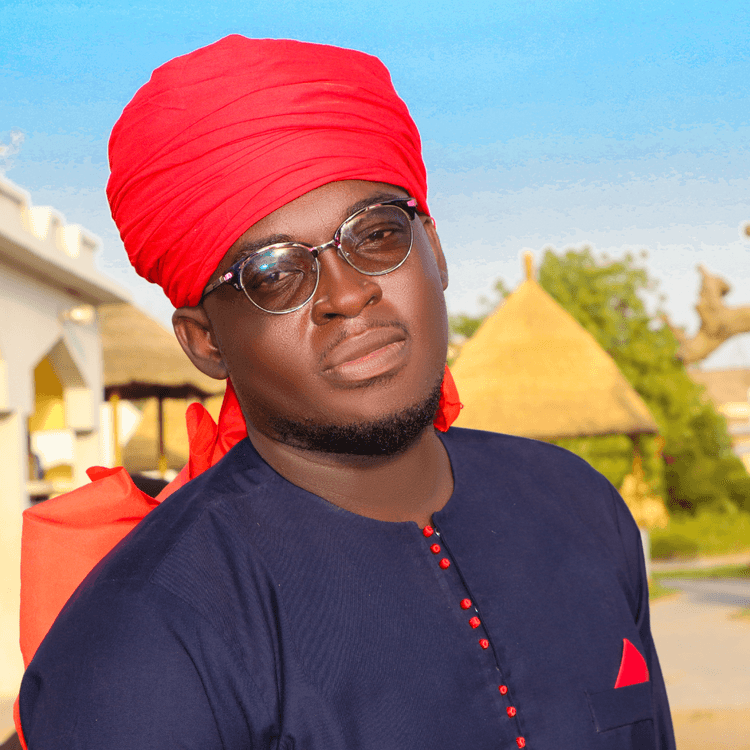

Alseny Farinta Camara, a symbol of democratic struggle

An AfricTivistes volunteer and a prominent member of Guinean civil society, he embodies a generation of activists for whom civic engagement remains highly meaningful, even when it comes at a significant personal cost. A dedicated political scientist, he reflects on his journey, his struggles and his imprisonment, as well as his vision for a fairer, more democratic and transparent Guinea. His activism encompasses the promotion of participatory governance at the local level, opposition to Alpha Condé’s third term in office, defence of human rights and mobilisation of young people.

AfricTivistes: You volunteered with AfricTivistes as part of the AfricTivistes Volunteers for Open and Participatory Local Governance (VAGOA) programme. How did this experience influence your path as an activist and your commitment to open local governance and citizen participation in Guinea?

Alseny F. Camara : Since 2018, AfricTivistes has trained, supported and equipped me through digital security training, active citizenship and digital accounts’ management. As a VAGOA, I was recruited alongside seven other nationalities from a pool of over 350 candidates to implement the Local Open GovLab (LOG) project in seven African countries. The project aimed to support, train and assist local authorities in adopting digital technology to promote inclusive and participatory governance. The project was based on a six-month assisted open local governance programme first to Mantakari in Niger then transferred to Kouroussa in particular. I gained new experiences and knowledge, which strengthened my commitment to communities. However, even before the LOG project, I had worked extensively with the National Platform of Citizens United for Development (PCUD) on democratic governance in local communities in my own country.

Reflecting on your extensive involvement in civil society, how would you define AfricTivistes as a pan-African organisation? What specific role do you believe it plays in promoting democracy and digital rights in Africa?

In my view, AfricTivistes is one of the most effective pan-African organisations addressing issues of democratic governance and the promotion of human rights and civil liberties in relation to digital technology. Beyond this, I find it to be highly dynamic and proactive on matters of continental importance, particularly when the principles of democracy, human rights and fundamental freedoms are threatened by African governments. This approach is essential to the vitality of the pan-Africanism I dream of, which is far removed from the sovereignist and populist rhetoric based on hatred, manipulation and rejection of others. I am eager to take advantage of every opportunity that AfricTivistes provides to continue learning, managing and sharing in an era of artificial intelligence, which demands considerable adaptation.

You transitioned from being an activist in associations to being at the forefront of political protests. When did you realise that civic engagement in Guinea had become an act of resistance?

I do believe civic engagement, a cornerstone of active citizenship, became an act of resistance in Guinea during the widespread mobilisation of society against President Alpha Condé’s attempt in 2020 to secure a third term in violation of the 2010 Constitution. I witnessed the defence and security forces acting with extreme brutality against pro-democracy activists. We have documented at least 90 people being shot dead and hundreds more being wounded or disabled for life, yet to date, the justice system has not shed any light on the matter. We defended a constitution that gave us the right to resist oppression in Article 4. This provision provided us with the legal motivation to resist power abuses and multiple serious violations of citizens’ rights. Through this act, we aimed to ensure the first peaceful democratic transition in Guinea. Alas!

The formation of the Front national pour la défense de la Constitution (FNDC) (National Front for the Defence of the Constitution) was a historic turning point in the fight against a third term. In retrospect, despite the price paid in terms of freedom, would you have made exactly the same choices?

As I said on the Africa 2015 programme on Nostalgie FM radio when I was released from Kindia civil prison on 19 December 2019, if this noble, legitimate and virtuous struggle were to be repeated, I would lead it with dignity. This is because I believe in selflessly committing to serving the public interest. All societies that have experienced positive and lasting change owe it to individuals or groups committed to the values of ethics, transparency and accountability. It is in this spirit of citizenship that I wish to contribute meaningfully to building a Guinean society based on social justice, transparency and accountability.

Your imprisonment in 2019 aroused widespread shock and concern both nationally and internationally. What are the human and political implications of being deprived of one’s freedom because of one’s beliefs?

Personally, it was mind-boggling to be deprived of my freedom for my convictions. First, I would like to use this opportunity to express my deepest gratitude to AfricTivistes, Amnesty International, Freedom House, Front Line Defenders, Human Rights Watch, Tournons La Page, and the entire international community for their solidarity. I remember the day I was kidnapped alongside my fellow activists on 4 November 2019. I trembled with fear in Kindia Civil Prison even before I was put in my cell. The deputy prosecutor and two judicial police officers came to question me in the prison commander’s office. They informed me of my rights and responsibilities as a political prisoner. After my first trial at the lower court, I was upset in my cell by the behaviour of a prison officer who deliberately spat on my shoes. When I protested, he replied in a commanding tone, ‘You are a prisoner. Here, you belong to the State. Not to yourself! What the State wants is what we will do to you.” Despite the soothing presence of the cell leader, I felt as if I was in an entirely different and more antagonistic environment.

You have experience of working on local governance, budget transparency and documenting human rights violations. In your opinion, what is the main obstacle to democracy in Guinea today?

I believe there are several factors that have hindered the democratic process in Guinea since 1958. Examples include ethnocentrism, the personalisation of power, systemic corruption, restrictions on fundamental freedoms, and recurrent human rights violations. Reflecting on my own background, I believe that ethnocentrism or regionalism should not be an end in itself. Instead, they should be recognised as a source of national cultural wealth, promoted without becoming entangled in a form of communitarianism that hinders the development of a peaceful and dynamic democracy in our sub-region. I am often outraged to see certain Guinean elites pitting ethnic groups or regions against each other, or victimising them, to satisfy their thirst for power and positions of responsibility. Consequently, citizen dynamics and public development policies are generally assessed from an ethnic or regionalist perspective rather than in terms of their positive impact on the Guinean population.

The crackdown on critical voices remains a consistent feature of life in the Republic of Guinea. In an environment that is increasingly hostile to civil liberties, how can activists and civil society organisations safeguard themselves?

We must be honest with ourselves. The Guinean State acts like a thug, suppressing critical voices. All these regimes have one thing in common: they are responsible for violent crimes, the arbitrary arrest and detention of dissidents, serious injuries, torture, inhuman and degrading treatment, arbitrary abductions, extrajudicial executions and enforced disappearances. As for activists, the luckiest are forced into exile, while the less fortunate are victims of enforced disappearances. In the most tragic cases, pro-democracy activists are killed by the defence and security forces. I consider these practices to be unacceptable, inconceivable and intolerable. Networking and solidarity between activists, international humanitarian institutions, organisations and citizen movements are essential for establishing democratic governance and promoting human rights sustainably.

You are a political science major. Does theory help you survive the brutality of activism, or does activism render theory irrelevant?

In my view, the lessons learned at university and the successful experiences gained in the field complement each other. They help me to maintain balance, define clear objectives and convictions and remain lucid in any civic endeavour. I believe civic-mindedness and initiatives are vital for strengthening the participation of young people and women in improving democratic governance.

Through your project, ‘My Job is My Business’, you addressed the issue of irregular migration. But can we really talk about chosen migration in a context of failed governance?

This citizen project is indeed the result of my experience working on construction sites in Conakry during my time at university. The situation today is as bitter as ever. There are young people and women in our neighbourhoods who have finished their studies. Some have been waiting for more than 5 to 10 years. They have not yet had their first internship, let alone a job. Some are dying in forests, deserts and the Mediterranean while attempting to reach the West. This is why I have started organising activities to raise awareness and encourage networking among young people at universities in Conakry. I want to inspire my generation to commit to the well-being of their community through community activities or social entrepreneurship. I consider irregular migration as one of the consequences of poor governance in our country. I believe that our leaders must invest in the potential of young people and women to prevent a massive brain drain, arbitrarily referred to as “chosen migration”.

Young people often find themselves at the forefront of protests, yet they are rarely present at the decision-making table. How can we channel the rebellious energy of young people into sustainable political power?

In my view, this is the greatest challenge facing young people today. There is an old saying that ‘young people are the future of a country’. However, I believe that young people are the present. They are at the forefront of all civic and political protests, yet excluded from decision-making tables. Governments do everything they can to curb the ambitions of young people and youth movements by imposing constraints – legal, economic and financial. In Guinea, for instance, the new constitution introduced by the military regime requires presidential candidates to be at least 40 years old. This contradicts the African Union’s Youth Charter. Therefore, we must continue to fight and organise with a clear vision of Guinea today and tomorrow, setting SMART objectives to promote the establishment of a peaceful and dynamic democracy that focuses on the socio-economic and cultural development of our country. Because, right now, those in Guinea who claim to act in the interests of young people and women are nothing more than obstacles or impostors.

You are known for your fight against corruption and illegal accumulation of wealth. Do you think corruption in Guinea is primarily a problem of legislation, political will, or civic culture?

Corruption and the illegal accumulation of wealth are endemic in Guinea. They have become part of the DNA of public officials. These practices are supported and encouraged by their families. This is not a problem of laws, but of political will. The Guinean military regime is steeped in corruption and nepotism. When I launched the initiative to oversee public action in November 2023, for example, to denounce acts of corruption and illegal accumulation of wealth, no one was prosecuted by the Court for the Suppression of Economic and Financial Offences (CRIEF) because they had all pledged allegiance to the authoritarianism and creeping dictatorship of the military regime. There are double standards in the fight against corruption in Guinea. According to the law on the prevention, detection and punishment of corruption and related offences, the presidents of republican institutions and ministers are required to declare their assets and property before the Supreme Court. In June 2024, I wrote to the Supreme Court to request access to the asset declaration forms of senior State officials. Unfortunately, I did not receive a single response. Corruption permeates the entire governance chain of the military regime, particularly public procurement procedures. In February 2024, for example, the Minister of Justice and Human Rights instructed the Attorney General of the Conakry Court of Appeal and the Special Prosecutor of the Court for the Suppression of Economic and Financial Offences (CRIEF), to investigate public contracts awarded under the CNRD regime. He stated that, during the 2022 financial year, the State had awarded 498 contracts through competitive bidding, 290 contracts by mutual agreement, and 2,475 contracts through requests for quotations. However, no action has yet been taken by the justice system.

In the face of authoritarianism, militant fatigue and disillusionment, what’s stopping you from giving up today?

(Smile😊!) To be honest, I love what I’m doing for my country. Despite the threats hanging over my head, I am holding on. I would like to reassure you that my struggle for democracy, social justice, transparency and accountability in Guinea will not be interrupted by discouragement or sheer exhaustion. Every day, I will strive to bring about the fall of dictatorship and authoritarianism. As the former Malian Minister of Justice, Maître Konaté, wrote in one of his columns, “To renounce the democratic struggle is to betray the people”. To remain silent is to be complicit. To resist is freedom.” I continue to fight in honour of all victims of State injustice and to ensure that justice prevails throughout Guinea.

In conclusion, your journey seems to embody the idea that ‘democracy is not begged for, it is conquered’. In light of the repression and democratic setbacks you have experienced, what does it mean to conquer democracy in Guinea today, and what message would you give to those who remain hesitant about getting involved?

We must be conquerors of democracy. It is important to remember that democracy is an ongoing process. It is built every day by men and women who love freedom and social justice. We must not lose sight of our rights and responsibilities in society. In the United States, for example, they have had more than two hundred years of democratic practice, yet today a trend is threatening the foundations of American democracy. Europeans, too, have more than two thousand years of democratic practice behind them. Alas! Today, we are witnessing the rise of political parties and movements that are hostile to democratic rights. In Africa, and in Guinea in particular, we boast only around sixty years of democratic practice. As former Nobel Peace Prize winner As a former Nobel Peace Prize winner Aung San Suu Kyi, said, “democracy is a universal heritage”. Therefore, it is essential for our generation to learn from other countries and commit wholeheartedly to promoting democracy, social justice, transparency, and accountability.

By Ndeye Fatou Diouf, Digital Content Manager at AfricTivistes

![[Gabon] AfricTivistes Sound the alarm amid Social Media suspension !](/static/6d29d22415421f36644f996c6396d73b/9e635/CREA-visuel-rapide-1.jpg)

![[SENEGAL] AfricTivistes strongly condemns the brutal repression of students at Cheikh Anta Diop University in Dakar!](/static/29c233858b9d650cc77d87f75d4d2b56/9e635/Ucad-Senegal.jpg)

![[Guinea-Bissau]: Joint Statement from Human Rights Defenders Against the Confiscation of Popular Will !](/static/8552596543d1c00bc73e662f85c0a62f/fce2a/Capture-decran-2025-12-01-a-16.34.43.png)

![[Guinée-Bissau] Joint Declaration – Afrikajom Center and AfricTivistes both firmly condemn the military takeover and warn of the risk of a political crisis !](/static/4d5ad12346b3ef8c55278621c445488b/9e635/Putsch-Guinee-2.jpg)

![[Tanzanie] 🇹🇿 AfricTivistes strongly condemns violent suppression in Tanzania](/static/adf91a1c13cd101f988b6b6971928880/9e635/TZN.jpg)

![[Cameroon] AfricTivistes condemns violent repression, urges govt to uphold rights !](/static/6399a9d8e94e3ae1f681f86178520d96/9e635/WhatsApp-Image-2025-10-27-at-15.32.48.jpg)

![[Madagascar] Generation Z, the driving force of civic awakening!](/static/9072e289fdab44c062096dcfb9499441/9e635/4-2.jpg)